Dutch elm disease

| Dutch elm disease | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Subdivision: | Pezizomycotina |

| Class: | Sordariomycetes |

| Order: | Ophiostomatales |

| Family: | Ophiostomataceae |

| Genus: | Ophiostoma |

Dutch elm disease (DED) is a fungal disease of elm trees which is spread by the elm bark beetle. Although believed to be originally native to Asia, the disease has been accidentally introduced into America and Europe, where it has devastated native populations of elms which had not had the opportunity to evolve resistance to the disease. The name Dutch elm disease refers to its identification in the Netherlands in 1921; the disease is not specific to the Dutch Elm hybrid [1][2]

Contents |

Overview

The causative agents of DED are ascomycete microfungi. Three species are now recognized: Ophiostoma ulmi, which afflicted Europe in 1910, reaching North America on imported timber in 1928, Ophiostoma himal-ulmi [3], a species endemic to the western Himalaya, and the extremely virulent species, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, which was first described in Europe and North America in the 1940s and has devastated elms in both areas since the late 1960s [4]. The origin of O. novo-ulmi remains unknown but may have arisen as a hybrid between O. ulmi and O. himal-ulmi [5] The new species was widely believed to have originated in China, but a comprehensive survey there in 1986 found no trace of it, although elm bark beetles were very common [5].

The disease is spread in North America by two species of bark beetles (Family: Curculionidae, Subfamily: Scolytinae): the native elm bark beetle, Hylurgopinus rufipes, and the European Elm Bark Beetle, Scolytus multistriatus. In Europe, while the aforementioned Scolytus multistriatus again acts as vector for infection, it is much less effective than the Large Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus scolytus.

In an attempt to block the fungus from spreading further, the tree reacts by plugging its own xylem tissue with gum and tyloses, bladder-like extensions of the xylem cell wall. As the xylem (one of the two types of vascular tissue produced by the vascular cambium, the other being the phloem), delivers water and nutrients to the rest of the plant, these plugs prevent them from travelling up the trunk of the tree, eventually killing it. The first symptom of infection is usually an upper branch of the tree with leaves starting to wither and yellow in summer, months before the normal autumnal leaf shedding. This progressively spreads to the rest of the tree, with further dieback of branches. Eventually, the roots die, starved of nutrients from the leaves. Often, not all the roots die: the roots of some species, notably the English Elm Ulmus procera, put up suckers which flourish for approximately 15 years when they too succumb.[4]

Disease range

Europe

Dutch elm disease was first noticed in Europe in 1910, and spread slowly, reaching Britain in 1927. This first strain was a relatively mild one, which only killed a small proportion of elms, more often just killing scattered branches, and had largely died out by 1940 owing to its susceptibility to viruses. The disease was isolated in The Netherlands in 1921 by Bea Schwarz, a pioneering Dutch phytopathologist, and this discovery would lend the disease its name.[6]

Circa 1967, a new, far more virulent strain arrived in Britain on a shipment of Rock Elm logs from North America, and this strain proved both highly contagious and lethal to European elms; more than 25 million trees have died in the UK alone. The disease is still migrating northwards through Scotland encouraged by global warming (the bark beetles will not fly in temperatures below 24° C), reaching Edinburgh in the 1980s, and Inverness in 2006. By 1990, very few mature elms were left in Britain or much of continental Europe. One of the most distinctive English countryside trees, the English Elm U. procera Salisb. (see John Constable's painting The Hay Wain), is particularly susceptible. 30 years after the outbreak of the epidemic, nearly all these magnificent trees, which often grew to > 45 m high, are gone. The species still survives in hedgerows, as the roots are not killed and send up root sprouts ("suckers"). These suckers rarely reach more than 5 m tall before succumbing to a new attack of the fungus. However, established hedges kept low by clipping have remained apparently healthy throughout the nearly 40 years since the onset of the disease in the UK.

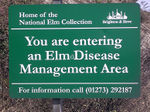

The largest concentration of mature elm trees remaining in England is in Brighton & Hove, East Sussex, where 15,000 elms still stand (2005 figures), several of which are estimated to be over 400 years old. Their survival is owing to the isolation of the area, between the English Channel and the South Downs, and the assiduous efforts of local authorities to identify and remove infected sections of trees immediately they show symptoms of the disease.[6] Empowered by the Dutch Elm Disease (Restriction on Movement of Elms) (Amendment) Order 1988 [7], local authorities may order the destruction of any infected trees or timber, although in practice they usually do it themselves, successfully reducing the numbers of elm bark beetle Scolytus spp, the vector of Elm Disease.[8]

United States

The disease was first reported in the United States in 1928, with the beetles believed to have arrived in a shipment of logs from the Netherlands destined for use as veneer in the Ohio furniture industry. The disease spread slowly from New England westward and southward, almost completely destroying the famous Elms in the 'Elm City' of New Haven, reaching the Detroit area in 1950 [9], the Chicago area by 1960, and Minneapolis by 1970.

Canada

Dutch elm disease reached Eastern Canada during the Second World War, and spread to Ontario in 1967, Manitoba in 1975 and Saskatchewan in 1981. The largest American, or American White, Elm Ulmus americana known to exist in Ontario, the Sauble Elm, succumbed to the disease and was cut down in September 1968 [10]. In Toronto, Ontario, 80% of the elm trees have been lost to Dutch elm disease; many more have fallen victim in Ottawa, Montreal and other cities during the 1970s and 1980s. Quebec City still has about 21,000 elms, thanks to a prevention program initiated in 1981[7]. Alberta and British Columbia are the only provinces that are currently free of Dutch elm disease, although an elm tree in southeastern Alberta was found diseased in 1998 and was immediately destroyed before the disease could spread any further. Thus, this was an isolated case. Today, Alberta has the largest number of elms unaffected by Dutch elm disease in the world. Aggressive measures are being taken to prevent the spread of the disease into Alberta as well as further progression of the disease in other parts of Canada. The City of Edmonton has banned elm pruning from March 31 to October 1, since fresh pruning wounds will attract the beetles during the warmer months.

Treatment

The first fungicide used for preventive treatment of Dutch elm disease was Lignasan BLP (carbendazim phosphate), which was introduced in the 1970s. This had to be injected into the base of the tree using specialized equipment, and was never especially effective. It is still sold under the name "Elm Fungicide". Arbotect (thiabendazole hypophosphite) became available some years later, and it has been proven effective. Arbotect must be injected every 2 to 3 years to provide ongoing control; the disease generally cannot be eradicated once a tree is infected.

Alamo (propiconazole) has become available more recently and shows some promise, though several university studies show it to be less effective than Arbotect treatments. Alamo is primarily recommended for treatment of Oak Wilt.

Treatment of diseased trees is costly and at best will prolong the life of the tree by perhaps five or ten years. It is usually only justified when a tree has unusual symbolic value or occupies a particularly important place in the landscape.

Practical information for elm tree owners

DED is caused by a fungus. It is primarily spread in three ways:

- By beetle vectors which carry the fungus from tree to tree — the beetle doesn't kill the tree, the fungus it carries does.

- Through direct contact of an infected tree's roots with a neighboring healthy tree.

- By pruning of a healthy tree with saws which have been used to take down diseased trees. This third method of spread is common and not recognized by many tree pruning and removal services. Arborists at Kansas State University claim that cleaning blades with a 10% solution of a household bleach will prevent this type of spread. Owners of healthy trees should be vigilant about the companies they hire to prune healthy trees. Blades need to be disinfected between use to remove dead trees and use to prune healthy trees.

Resistant trees

Research to select resistant cultivars and varieties began in the Netherlands in 1928, followed by the USA in 1937. Initial efforts in the Netherlands involved crossing varieties of U. minor and U. glabra, but later included the Himalayan or Kashmir Elm U. wallichiana as a source of anti-fungal genes. Early efforts in the USA involved the hybridization of the Siberian Elm Ulmus pumila with American elms to produce resistant trees, but ones lacking the beauty, traditional shape, and landscape value of the American Elm; few were planted.

In 2005 the National Elm Trial (USA) began a 10-year evaluation of 19 cultivars in plantings across the United States. The trees in the Trial are exclusively American developments; no European cultivars have been included.

Recent research in Sweden has established that early-flushing clones are less susceptible to DED owing to an asynchrony between DED susceptibility and infection [8].

Cultivars

Ten resistant American Elm U. americana cultivars are now in commerce in North America, but only one ('Princeton') is currently available in Europe, although several more should be in commerce in the UK from 2012. Notable trees include:

- 'Valley Forge', which has demonstrated the highest resistance of all the clones to Dutch elm disease in controlled USDA tests.

- 'Princeton', a cultivar selected in 1922 by Princeton Nurseries for its landscape merit. By happy coincidence, this cultivar was found to be highly resistant in inoculation studies carried out by the USDA in the early 1990s. As trees planted in the 1920s still survive, the properties of the mature plant are well known.

- 'Lewis & Clark' (Prairie Expedition TM ), the latest cultivar to be released in 2004, cloned from a tree found growing in North Dakota which had survived unscathed when all around had succumbed to disease.

There is also 'American Liberty', in fact a set of six cultivars of moderate to high resistance produced through selection over several generations starting in the 1970s. Although 'American Liberty' is marketed as a single variety, nurseries selling the "Liberty Elm" actually distribute the six cultivars at random and thus, unfortunately, the resistance of any particular tree cannot be known. One of the cultivars, 'Independence', is covered by patent (U. S. Plant Patent 6227).

In 2007, the Elm Recovery Project from the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada reported that cuttings from healthy surviving old elms surveyed across Ontario had been grown to produce a bank of resistant trees, isolated for selective breeding of highly resistant cultivars [11] .

The University of Minnesota USA is testing various elms including a huge now-patented century old survivor known as "The St. Croix Elm" which is located in a Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN suburb (Afton) in the St. Croix ("kroy") River valley — a designated National Scenic Riverway.

The Slippery or Red Elm U. rubra is marginally less susceptible to Dutch elm disease than the other American species, but this quality seems to have been largely ignored in American research. No cultivars were ever selected, although the tree was used in hybridization experiments resulting in the release of 'Coolshade' and 'Rosehill' in the 1940s and 50s. The species last featured in hybridization as the female parent of 'Repura' and 'Revera', both patented in 1993, although neither has yet appeared in commerce.

Other species to feature in the American DED research programmes were the Siberian Elm U. pumila, Japanese Elm U. davidiana var. japonica, and the Chinese Elm U. parvifolia, giving rise to several dozen cultivars resistant not just to DED but to the extreme cold of that continent's winters.

No cultivar is immune to DED; even highly resistant cultivars can become infected, particularly if already stressed by drought or other environmental conditions where the disease prevalence is high. With the exception of the Princeton Elm, no trees have yet been grown to maturity. The oldest 'American Liberty' elm was planted in about 1980, and the trees cannot be said to be mature until they have reached an age of 60 years.

In 2001, English Elm U. procera was genetically engineered to resist disease, in experiments at Abertay University, Dundee, Scotland, by transferring anti-fungal genes into the elm genome using minute DNA-coated ball bearings [12]. However, owing to the hostility to GM developments, there are no plans to release the trees into the countryside.

Hybrid cultivars

There have been many attempts to breed disease resistant cultivar hybrids and they have usually involved a genetic contribution from Asian elm species which have demonstrable resistance to this fungal disease. Much of the early work was undertaken in the Netherlands. The Dutch research programme began in 1928 and ended after 64 years in 1992, during which time well over 1000 cultivars were raised and evaluated. The programme had three major successes: 'Columella', 'Nanguen' LUTÈCE, and 'Wanoux' VADA [9], all found to have an extremely high resistance to the disease when inoculated with unnaturally large doses of the fungus. Only 'Columella' was released during the lifetime of the Dutch programme, in 1987; patents for the LUTÈCE and VADA clones were purchased by the French Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), which subjected the trees to 20 years of field trials in the Bois de Vincennes, Paris, before releasing them to commerce in 2002 and 2006 resp.

In Italy, research is continuing at the Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante, Florence, to produce a range of disease-resistant trees adapted to the warmer Mediterranean climate, using a variety of Asiatic species crossed with the early Dutch hybrid Plantyn (elm hybrid) as a safeguard against any future mutation of the disease [10]. Two trees with very high levels of resistance; 'San Zanobi' and 'Plinio' [11] were released in 2003. 'Arno' and 'Fiorente' were patented in 2006 and will enter commerce in 2012. All four have the Siberian Elm Ulmus pumila as a parent; the source of disease-resistance and drought-tolerance genes. Further releases are planned, notably of a clone derived from a crossing of Dutch Elm Ulmus × hollandica with the Chinese species Ulmus chenmoui.

The European White Elm

There is also the unique example of the European White Elm U. laevis which has little innate resistance to Dutch elm disease but is eschewed by the vector bark beetles and only rarely becomes infected. Recent research has indicated that it is the presence of certain organic compounds, such as triterpenes and sterols, which serves to make the tree bark unattractive to the beetle species that spread the disease [12].

Possible earlier occurrences

A less devastating form of the disease, caused by a different fungus, had possibly been present in Britain for some time, as this passage in Richard Jefferies' 1883 book, Nature near London, shows:

- There is something wrong with elm trees. In the early part of this summer, not long after the leaves were fairly out upon them, here and there a branch appeared as if it had been touched with red-hot iron and burnt up, all the leaves withered and browned on the boughs. First one tree was thus affected, then another, then a third, till, looking round the fields, it seemed as if every fourth or fifth tree had thus been burnt. [...] Upon mentioning this I found that it had been noticed in elm avenues and groups a hundred miles distant, so that it is not a local circumstance.

Though dead elms also appear in Italian paintings of the late 15th century, this suggestion remains largely speculative, and there is no proof that it was caused by a fungus related to Dutch elm disease.

From analysis of pollen in peat samples, it is apparent the elm all but disappeared from Europe during the mid-Holocene period about 6000 years ago, and to a lesser extent 3000 years ago. Examination of sub-fossil elm wood has suggested that Dutch elm disease may have been responsible.[13]

References

- ↑ Forestry Commission. Dutch elm disease in Britain [1], UK.

- ↑ Macmillan Science Library: Plant Sciences. Dutch Elm Disease

- ↑ Brasier, C. M. & Mehotra, M. D. (1995). Ophiostoma himal-ulmi sp. nov., a new species of Dutch elm disease fungus endemic to the Himalayas. Mycological Research 1995, vol. 99 (2), pp. 205-215 (44 ref.) ISSN 0953-7562. Elsevier, Oxford, UK.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Spooner B. and Roberts P. 2005. Fungi. Collins New Naturalist series No. 96. HarperCollins Publishers, London

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Brasier, C. M. (1996). New horizons in Dutch elm disease control. Pages 20-28 in: Report on Forest Research, 1996. Forestry Commission. HMSO, London, UK.[7]

- ↑ Brighton and Hove Council page on the city's elm collection (viewed 2 June 2010)

- ↑ Contact, Laval University, Volume 28, Number 1

- ↑ Ghelardini, L. (2007) Bud Burst Phenology, Dormancy Release & Susceptibility to Dutch Elm Disease in Elms (Ulmus spp.). Doctoral Thesis No. 2007:134. Faculty of natural Resources and Agricultural Services, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden

- ↑ Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique. Lutèce, a resistant variety, brings elms back to Paris [2], Paris, France

- ↑ Santini A., Fagnani A., Ferrini F., Mittempergher L., Brunetti M., Crivellaro A., Macchioni N., Elm breeding for DED resistance, the Italian clones and their wood properties. Invest Agrar: Sist Recur For (2004) 13 (1), 179-184. 2004. [3]

- ↑ Santini A., Fagnani A., Ferrini F. & Mittempergher L., (2002) San Zanobi and Plinio elm trees. HortScience 37(7): 1139-1141. 2002. American Society for Horticultural Science, Alexandria, VA 22314, USA.

- ↑ Martín-Benito D., Concepción García-Vallejo M., Alberto Pajares J., López D. 2005. Triterpenes in elms in Spain. Can. J. For. Res. 35: 199–205 (2005). [4]

- ↑ [5]

External links

- Elm Recovery Project - Guelph University (Canada)

- Dutch elm disease - info from the Government of Alberta

- Dutch elm disease - info from the Government of British Columbia

- DED info from Rainbow Treecare Scientific Advancements

- The Mid-Holocene Ulmus decline: a new way to evaluate the pathogen hypothesis

- KIM PALMER, Minneapolis, Minnesota USA Star Tribune